The Barracco Collection

In the first catalogue of the collection, published in 1893, Barracco sets out the principles that govern his collection: “I thought that to learn more about Greek art one should get acquainted with the oldest art styles (Egypt and Asia) who gave the first impulse to Greek art. So I broadened my collection with a few instructive specimens of Egyptian, Assyrian and Cypriot sculpture.

Taking advantage of favourable circumstances I have set up a small museum of comparative antique sculpture. So, apart from minor shortcomings, which I hope to overcome, the most important styles are conveniently represented: Egyptian art in all its stages, from the age of the pyramids to the loss of independence, Assyrian art in its two periods: that of Assur-nazir-Habal and that of Sargonidesm, and finally the art of Cyprus, which is not less important than the others. Greece is represented from the archaic period, the great schools of the V and IV centuries, to the Hellenistic period. Etruria is equally represented. A small place is reserved to Palmyrene sculpture, one of the last expressions of classical art.”

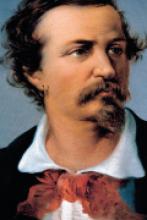

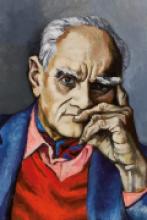

For his ambitious project, Barracco recruited two experts in ancient art of the time: Wolfgang Helbig, second secretary of the German Archaeological Institute, then retired to private life in the beautiful Villa Lante on the Janiculum Hill, where he took active part to the city’s ‘arts and antiques’ environment; and Ludwig Pollak, who had moved to Rome after having studied archaeology in Vienna, and where he became a major player in the cultural life of the city, especially in the antiquities trade. Pollak, whose interests ranged from classical to modern art, soon became a close friend and fine art advisor.

The collection, carefully arranged to set up “a museum of comparative antique sculpture” includes works of Egyptian, Assyrian, Phoenician, Cypriot, Etruscan, Greek, Roman and medieval art.

As for Egyptian art, to which Barracco dedicated more of himself than to any other, the collection includes remarkable fragments of funerary sculpture, especially of the early dynasties.

Alongside these works, purchased on the international market, important items emerged during excavations of the nineteenth and early twentieth century in various Italian places enrich the collection: they give a detailed account of the Egyptian penetration in Italian culture since Roman times.

Noteworthy is the sphinx of Hatscepsut, a queen of the XVIII Dynasty (1479-1425 BC), found in the sanctuary of Isis in the Campus Martius, but also the head of Pharaoh Seti I (XIX Dynasty, 1289-1278 BC) reused as building material for the Savelli castle in Grottaferrata.

Assyrian art is represented by an important series of reliefs depicting scenes of war, the deportation of prisoners and hunting scenes, from the royal palaces of Nineveh, Nimrud and Khorsabad in northern Mesopotamia. The findings, which date from the IX to the VII centuries BC, relate to the major kings of the neo-Assyrian Empire.

Particularly significant is the fragment that reproduces the figure of a winged genius kneeling, a typical element of the mythic-symbolic language of Assyrian art, dating back to the reign of Ashurbanipal II (883-859 BC) and coming from Nimrud.

A particularly interesting section of the museum displays Cypriot artworks, revealing cross-cultural connections between the ancient Near East and the Greek world.

Figures of deities, such as the Statue of Heracles-Melqat (V century BC, ), images of offerers and even a small toy chariot found in a tomb, offer a unique chance to see Cypriot artworks in Rome.

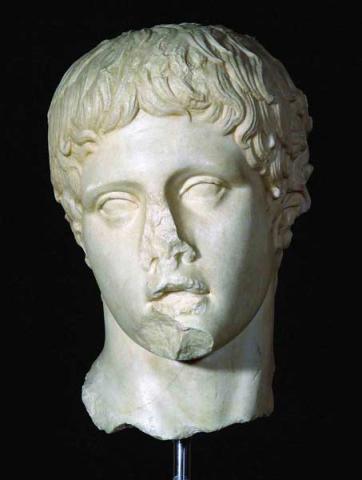

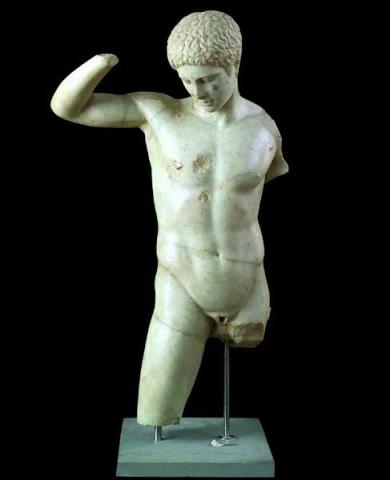

Besides some important Etruscan finds, Greek sculptures are the most represented in the Museum. Starting with important examples of archaic art made in Greece and in the western colonies, remarkable specimens of the major schools of classical Greek art: with copies of the highest level after Myron, Phidias, Polykleitos, Lysippus illustrate some of the most celebrated masterpieces of Greek sculpture of the V and IV centuries BC.

A special place is reserved to original Greek artworks, plenty for a relatively small collection. Through a series of Hellenistic artworks, visitors are guided through most expressive forms of Roman art: there are some portraits, the fragment of an important historical relief, a large head of Mars from a public monument, and some tombstones from Palmyra, Syria.

Two tiles from the Sorrento cathedral (X-XI century) and a Medieval fragment of apse mosaic of St. Peter's Basilica (XII-XIII century) are at the end of the exhibition path: "My collection ends here, several thousand years since its beginning, which dates back to the earliest dynasties of Egyptian kings”.

In 1902, in a gesture of great generosity, Barracco decided to donate to the City of Rome the entire collection of sculptures, which included nearly two hundred artworks: in return he was granted the use of a building land on Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, where the road meets the Tiber. On this land Barracco built a small neoclassical building designed by Gaetano Koch, with a facade like an Ionic temple according to the fashion of the time, whose pediment bore the inscription MVSEO DI SCVLTVRA ANTICA.

In the new Museum, which opened in 1905, the sculptures were arranged in two long exhibition halls, with large windows cut into the top of the walls to ensure proper lighting of the artworks similar to that the Baron had studied for his apartment on via del Corso; many sculptures were placed on elegant black wood swivel bases, especially designed to display artworks. Finally, it was the first museum in Italy to be equipped with a heating system to make the visit more pleasant .

The 1931 town planning and the amendments to the city’s urban area required the demolition of the building built by Koch only a few decades earlier: despite impassioned attempts by Pollak the Museum was demolished in 1938, artworks in the collection were moved to the Capitoline Museums warehouse until when, in 1948, the collection was finally moved to the present seat in the so-called “Farnesina ai Baullari”.