Etruscan art

The group of civilizations represented in the Barracco collection could hardly fail to include the Etruscan. In fact, though Barracco’s interests as a collector were mainly directed toward other horizons, the collection contains a few but significant examples of Etruscan art.

The works on display come from central Italy, in particular the vast area between the Arno River and the Tiber. In this area, Etruscan civilization developed with a culture and language of its own, starting in the 8th century B.C. and continuing until the Etruscans were definitively subjected by the Romans, at the end of the 2nd century B.C.

The oldest pieces in the collection date from the first decades of the 5th century. They come from Chiusi, a city that was part of the Etruscan dodecapolis, a sort of federation among the major city-states in the region. The other members were Veii, Caere, Tarquinia, Vulci, Roselle, Vetulonia, Populonia, Volterra, Volsinii, Perusia, Cortona, Arretium and Vipsul (or Visul, which some scholars identify as Fiesole).

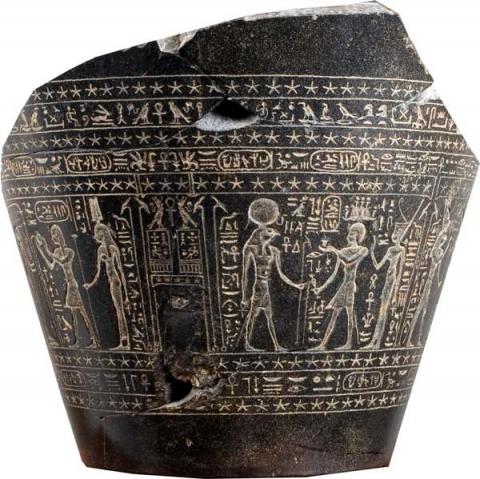

The characteristic funerary markers, carved from local stone, consist of elements assembled vertically and surmounted by a finial in the shape of a pine-cone or sphere The scenes that honor the deceased person – banquets, funeral games, dancing, mourning, battles – are sculpted in very low relief. They are marked by very strong Greek and eastern influences, a sign of the close cultural and commercial contacts between the Etruscans and the Greek world, especially via the Greek colonies in the West.

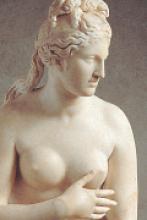

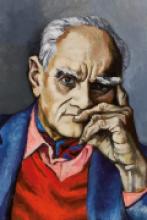

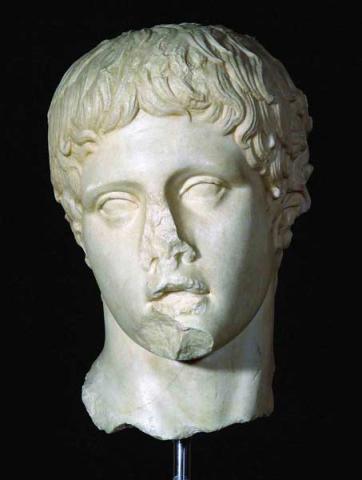

The two heads from Orvieto and Bolsena,, where they must have decorated monumental buildings, share a representational language decidedly influenced by the formal experiences of Hellenism. In the Orvieto head (MB 204), with its elaborate hairdo, the presence of a torque – an ornament typically worn by the Celtic populations of northern Italy – reflects the complexity of cultural relations and exchange among the different peoples that had settled the peninsula before the domination of Rome.